Interview with Kyle Barron on GeoArrow and GeoParquet, and the Future of Geospatial Data Analysis

Kyle Barron, Cloud Engineer at Development Seed.

You’ve spent years figuring out how to visualize large geospatial datasets in web browsers. Can you tell us a bit about your background and what initially drew you to this area?

I have a bit of a nontraditional background; I have virtually no official training in geography or computer science. In college, I was interested in urban and environmental economics, trying to understand how policies shape cities and the environment. I planned to pursue a PhD in economics and after college worked for a health economics professor at MIT for two years.

In that time I learned data analysis skills, but more importantly, I learned that I preferred data analysis and coding to academic research. I decided not to pursue a PhD and left that job to hike the Pacific Crest Trail, a 2,650-mile hiking trail from Mexico to Canada through California, Oregon, and Washington. Over five months of hiking, I had plenty of time for reflection and decided to try to switch to some sort of career in geospatial software or data analysis.

I didn’t particularly want to go back to school and had plenty of ideas to explore, so I decided to build a portfolio of projects and hopefully land a job directly. For seven months, my learning was self-directed in the process of making an interactive website dedicated to the Pacific Crest Trail. I learned core geospatial concepts like spatial reference systems and how to manage and join data in Python with GeoPandas and Shapely. I learned basic JavaScript, how to use and create vector tiles, and how to render basic maps online. All the content served from that website I figured out how to generate: OpenStreetMap-based vector tiles, a topographic map style, NAIP-based raster tiles, and USGS-based hillshade data and contour lines.

From the beginning, I was excited about the browser because of its broad accessibility. I wanted to share my passions with the non-technical general public. Everyone has access to a web browser while only domain specialists have access to ArcGIS or QGIS and know how to use them. Even today, if the Pacific Crest Trail comes up in conversation, I’ll pull up the website on my phone and show some of my photography on the map. Interactive web maps connect with the general public at a deeper level than any other medium.

These projects also led me to my first software job. As I was building my own applications, I also contributed bug fixes back to deck.gl and the recently-formed startup Unfolded offered me a job!

Let’s jump right into GeoParquet and GeoArrow. In layman’s terms, what are these tools, and why are they creating such a buzz in the geospatial data community?

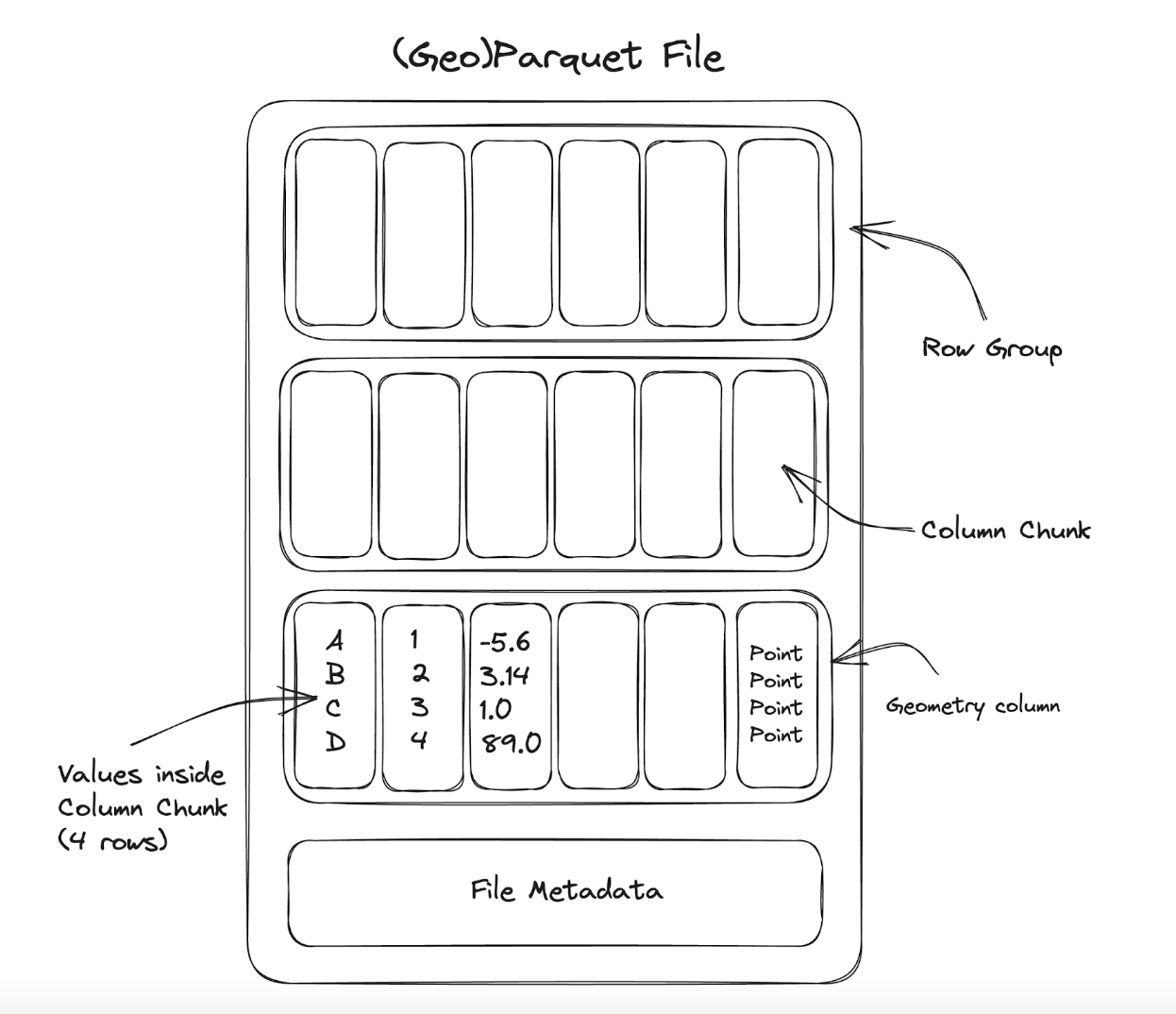

GeoParquet and GeoArrow are both ways to speed up handling larger amounts of geospatial data. Let’s start first with GeoParquet since that’s a bit more approachable to understand.

GeoParquet is a file format to store geospatial vector data, as an alternative to options like Shapefile, GeoJSON, FlatGeobuf, or GeoPackage. Similar to how Cloud-Optimized GeoTIFF (COG) builds upon the existing GeoTIFF and TIFF formats, GeoParquet builds upon the existing Parquet format for tabular data. This gives the GeoParquet format a head start because there are many existing libraries to read and write Parquet data that can be extended with geospatial support.

Three things excite me about GeoParquet: it’s cloud-native, so you can read relevant portions of the file directly from cloud storage, without downloading the entire file. It compresses very well and is fast to read and write, so even in non-cloud-native situations, it can speed up workflows. And it integrates well with other new technologies such as GeoArrow.

GeoParquet is cloud-native

GeoParquet 1.1 introduced support for spatial partitioning. This makes it possible to fetch only specific rows of a file according to a spatial filter.

Note that spatial partitioning is a slightly different concept to spatial indexing. In a format like FlatGeobuf or GeoPackage that performs spatial indexing, it records the position of every single row of your data. This is often useful when you want to quickly access individual rows of data, but it prevents effective compression and becomes harder to scale with large data because the index grows very large. In contrast, spatial partitioning uses chunking, where instead of indexing per row, it records the extent of a whole group of rows. This provides flexibility and scalability when writing GeoParquet data. By adjusting the chunk size, the writer can choose the tradeoff between index size and indexing efficiency.

The upside of spatial partitioning is that an entire group of data is indexed and compressed as a single unit. The downside is that if you do want to access only a single row, you’ll have to fetch extra data. The sweet spot is when you want to access a collection of data that’s co-located in one spatial region. (If your access patterns regularly care about single rows of data, a file format like FlatGeobuf or GeoPackage might be better suited to your needs. GeoParquet is tailored to bulk access to data.)

GeoParquet also lets you fetch only specific columns from a dataset. If the dataset contains 100 columns but your analysis only pertains to the geometry column plus 3 other columns, then you can avoid downloading most of the file. For example, with stac-geoparquet, a user might want to find URLs to the red, green, and blue bands of Landsat scenes within a specific spatial area, date range and cloud cover percentage. This query is much more efficient with GeoParquet because it only needs to fetch these six columns, not all of the dozens of attribute columns.

GeoParquet compresses effectively

GeoParquet also excels even when you don’t care about its cloud-native capabilities. It compresses extremely well on disk and is very fast to read and write. This leads GeoParquet to be used as an intermediate format for analysis, such as GeoPandas, where a user wants to back up and restore their data quickly.

For example, Lonboard, a Python geospatial visualization library I develop, uses GeoParquet under the hood to move data from Python to JavaScript. This isn’t a cloud-native use case, but GeoParquet is still the best format for the job because it compresses data so well and minimizes network data transfer.

GeoParquet’s integration with GeoArrow

GeoParquet is a file format; when you read or write GeoParquet you need to store it as some in-memory representation. This is where GeoArrow comes in. It’s a new way of representing geospatial vector data in memory and a way that’s efficient to operate on and fast to share between programs.

GeoParquet and GeoArrow are well integrated and have a symbiotic relationship, where the growing adoption of one makes the other more appealing. The fastest way to read and write GeoParquet is to and from GeoArrow. But GeoArrow is not strictly tied to GeoParquet: it can be paired with any file format.

For example, GDAL’s adoption of GeoArrow made it 23x faster to read FlatGeobuf and GeoPackage into GeoPandas. Historically, GeoPandas and GDAL didn’t have a way to share a collection of data at a binary level. So GDAL (via the fiona driver) would effectively create GeoJSON Python objects for GeoPandas to consume. This is horribly inefficient. Since GDAL 3.6, GDAL has supported reading into GeoArrow and since GDAL 3.8 it has supported writing from GeoArrow.

With the cloud playing a bigger role in data storage and processing, how can GeoParquet empower new users and unlock possibilities beyond traditional geospatial analysis?

I’m excited for the potential of GeoParquet and related technologies to replace or complement standalone databases. Existing collections of large geospatial data might use a database like PostGIS, which requires an always-on server to respond to user queries and a developer who knows how to maintain that system.

While Parquet itself is a read-only file format, there are newer technologies, like Apache Iceberg, that build on top of Parquet to enable adding, mutating, and removing data. People are discussing how to add geospatial support to Iceberg. In the medium term, Iceberg will be an attractive serverless method to store large, dynamic geospatial data that would be difficult or expensive to maintain in PostGIS.

We continue to see improved performance in both user devices and the cloud. How do you envision the future of geospatial data in web browsers? What kind of use cases would you like to see enabled?

Moving data is difficult and expensive and interacting with the cloud from browser applications presents interesting problems of data locality. Indeed, both user devices and the cloud are getting more powerful, but network connectivity, especially over the public internet, isn’t improving proportionally fast. That means there will continue to be a gulf between local, on-device compute, and cloud compute.

We’ve seen this phenomenon lead to the advent of hybrid data systems that span local and remote data stores. New analytical databases like DuckDB or DataFusion and new data frame libraries like Polars have the potential to work with data on the cloud in a hybrid approach, where only the portions of data required for a given query need to be fetched over the network.

I conclude that in the future there will be geospatial, browser-based hybrid systems. Non-technical users will navigate to a website and connect to all their local and cloud-based data sources. The system will intelligently decide which data sources to download and materialize into the browser. And it will connect to the tech underlying Lonboard, efficiently rendering that data on an interactive map.

I’ve been making steady progress towards this goal. Through the WebAssembly bindings of my geoarrow-rust project, I’ve been collaborating with engineers at Meta to access Overture GeoParquet data directly from the browser. Downloading an extract from the website will perform a spatial query of Overture GeoParquet data directly from S3 without any server involved.

In general, I find “data boundaries” to present fascinating problems. Both local and cloud devices are powerful, but moving data between those two domains is very slow. When do you need to move data across boundaries; how can you minimize what data you need to move, and how can you make the movement most efficient when you actually do need to move it?

Beyond technical expertise, what books, articles, podcasts, or even movies have significantly influenced your career path?

The specific experience with the largest non-technical influence on my career was my time hiking the Pacific Crest Trail. It piqued my interest in thinking about data for the outdoors and climate and gave me a strong base of motivation for learning how to work with geospatial data. I consider having motivation and ideas around what to create much more important than learning how to do something. There’s enough technical material on the internet to learn whatever you want. But you need the motivation to push yourself over that initial hump, the period where things just don’t make sense. It’s been really useful for my learning to have an end goal in mind that keeps me motivated to press on through the “valley of despair” of new concepts.

I’d also point to a video by prolific YouTuber and science communicator Tom Scott: “The Greatest Title Sequence I’ve Ever Seen.” It discusses an introductory sequence to a British TV show and notes how much attention to detail there was, even when virtually no one would notice all those details. I love this quote:

“Sometimes, it’s worth doing things for your craft, just because you can. That sometimes it’s worth going above and beyond, and sweating the small stuff because someone else will notice what you’ve done.”

I tend to be a perfectionist and strive for the best because I want it, not because someone else is asking for it. In my own career, I’ve noticed how attention to detail came in handy in unexpected ways. Where by going above and beyond in one project I learned concepts that made later projects possible.

I should also note that a collection of people online have been really strong influences. There are too many to name them all, but Vincent Sarago and Jeff Albrecht were two of the first people I met in the geospatial community and they’ve been incredible mentors. And the writings and code of people like Tom MacWright and Volodymyr Agafonkin have taught me so much.

Our blog is open source. You can suggest edits on GitHub.