The Admin-partitioned GeoParquet Distribution

So the last few months I embarked on a seemingly simple project – translate more data into GeoParquet to help its adoption. My modest goal to start was to try to be sure there’s ten or twenty interesting datasets in GeoParquet, so it’s easy to try it out with some practical projects. But I’ve gone down a deep rabbit hole of exploration, which is by no means finished and indeed feels barely started, but I wanted to share what I’m seeing and excited about.

The simple core of it is an approach for distributing large amounts of geospatial vector data, but I think there are potentially profound implications for things like ‘Spatial Data Infrastructure’ and indeed for our industry’s potential impact on the world. For this post I’m going to keep it focused on the core tech stuff.

I’ve explained a few aspects of what I’ve learned about GeoParquet and DuckDB in my quest to make the Google Buildings dataset more accessible. Most of that what I learned was actually fairly incidental to the main thing I was trying to figure out: whether there’s a way to distribute a large scale dataset in a way that’s accessible to traditional desktop GIS workflows, future-looking cloud-native queries, geospatial servers, and mainstream (non-geo) data science / data engineering tools. To be explicit on each:

- Traditional Desktop GIS Workflow – Go to a portal or website, navigate the folder structure to the country or state or other relevant area you care about, download and load it into your desktop GIS.

- Cloud-Native Queries – Enable streaming of just the data user cares about (location & other attributes) and efficiently return that for their analysis or visualization, using only HTTP (generally heavily relying on range requests)

- Geospatial Servers – Enable any higher level API (could be run in the cloud, in a dataset, even serverless) to treat the same data format as its ‘backend’ and serve up visualization & analysis through standard and non-standard interfaces.

- Mainstream (non-geo) data science & data engineering – Be easy to use in the new generation of mainstream data tools – BigQuery, Snowflake, RedShift, Presto/Athena, DataBricks, DuckDB, etc.

One of the beauties of the Cloud-Optimized GeoTIFF is that it is incredible for cloud-native queries – efficiently returning the location and just the requested bands of the raster image. But it’s also completely backwards compatible, as any COG could be loaded up in any traditional GIS tool. I don’t believe we’ll get anything so incredibly backwards compatible in the vector data world (I did pursue Cloud-Optimized Shapefile for a bit, but the only tool to actually order it right is buried in MapServer, and it’s got some serious problems as a format). But if we can teach QGIS (already done) and Esri (hopefully will happen before too long) to read GeoParquet then you can support that traditional workflow of downloading data and dropping it into the desktop. And to be clear, I don’t use ‘traditional’ to be dismissive or negative at all. It’s actually a really great workflow, and I use it all the time. I like streaming stuff, but I also like just having it on my computer to use whenever I want. I’m writing this on a plane right now, and it’s nice I can still explore locally.

The point upfront

So this is going to be a long-ass blog post going into all that I’ve explored, along with most of the ideas that I want to explore next. But I’ll start with the end for those who just want the tl;dr. I think there’s some great potential for GeoParquet partitioned by administrative boundaries to be an ideal vector data distribution format, especially when paired with STAC and PMTiles. In the course of working with Google Open Buildings data the first version of Overture data dropped, with Parquet as the core format. Awesome! Except it’s not GeoParquet, and it’s actually pretty hard to use in most of the workflows above. The team put together great docs for lots of options, but it wasn’t easy or fast to subset to an area you care about.

I wanted to try to help make that easy, so I had some good fun adapting what I’d learned from Google Buildings, and I’ve put up both the building and places datasets on Source Cooperative for each country as GeoParquet. If the country is big (over ~2 gigs) then I break it up by quadkey (more on that below). I’ve focused on GeoParquet, instead of putting up versions in GeoPackage, Shapefile, GeoJSON & FlatGeobuf. I think it’s hugely important to support those formats, but my idea has been to try out cloud-native queries that transform the data on the fly, instead of maintaining redundant copies in every format. And it works!

I’ve built an open source command-line tool, that takes a GeoJSON file as input and uses DuckDB to query the entire set GeoParquet dataset on source.coop, downloads just the buildings that match the spatial query and outputs them into the format the user chooses. You can check out a little demo of this:

This response time is ~6 seconds, but requires a user to supply the ISO code of the country their data is in (I have some ideas of how to potentially remove the need for the user to enter it). Without entering the ISO code the request scans the entire 127 gigabytes of partitioned GeoParquet data, and takes more like 30 seconds.

In many ways 30 seconds is a long time. But remember there is absolutely no server involved at all, and you are able to get the exact geospatial area that you care about. And in traditional GIS workflows the user would have to wait to download a 1.5 gigabyte file, which would take several minutes on even the fastest of connections.

The query just uses stats from the partitioning of Parquet to home in on the data needed, returns it to a little local, temporary DuckDB database, and uses DuckDB’s embedded GDAL to translate out into any format. If you request huge amounts of data through this then the speed of getting the response will depend on your internet connection.

Right now this is a command-line tool, but I’m pretty sure this could easily power a QGIS (or ArcGIS Pro) plugin that would enable people to download the data for whatever area they specify on their desktop GIS. If anyone is interested in helping on that I’d love to collaborate.

This tool should work against any partitioned GeoParquet dataset that follows a few conventions. There’s a few out there now:

- Google Buildings Cloud-Native Geospatial distribution: the geoparquet-by-country directory.

- Overture Buildings CNG distribution: the best one right now is the geoparquet-country-quad-hive/

- Microsoft Building Footprints : the original inspiration for all my work, see this discussion for the start of my journey down the rabbit hole. My CLI isn’t yet working against this data (issue #27), but it shouldn’t be hard after auth is figured out.

- Combined Google and Microsoft Buildings: released by VIDA, the by_country_s2/ is the better directory, not yet working with the CLI (issue #26)

- Overture Places CNG distribution, part of the Overture buildings mentioned above, available at places-geoparquet-country/ directory.

Most of these are over 80 gigabytes of GeoParquet data, and they’d be even larger if they were more traditional formats. Right now the CLI only works with the first two, using a ‘source’ flag, but I’m hoping to quickly expand it to cover the others, as only minor tweaks are needed.

The other thing that’s worth highlighting is that if you just want to visualize the data you can easily use PMTiles. It’s an incredible format that is completely cloud-native and gives the same web map tile response times you’d expect from a well-run tile server.

The Admin-Partitioned GeoParquet Distribution

So I wanted to describe the core thing that makes this all work. It could probably use a snappy name, but my naming always tends towards the straight forward description. I suspect there’s many things to optimize, and ideally we get to an set of tools that makes it easy to create an Admin-partitioned GeoParquet distribution from any (large) dataset.

One main bit behind it is Parquet’s ‘row groups’, which are done at the level of each file, breaking it up into chunks that can report stats on the data within them. These can both be used in a ‘cloud-native’ pattern – querying the ‘table of contents’ of each file with an http range request to figure out what, if any, of the data is needed, enabling efficient streaming return of just the data collected. For many other formats that table of contents is in the header, for Parquet it’s actually the footer, but it works just as well. I’m far from the expert on this stuff, so if anyone has a good explanation of all this that I can link to let me know.

Building on the row groups, the other main innovation the ability of most tools to treat a set of Parquet files as a single logical dataset, using ‘hive partitioning’. I believe the core idea behind this was to have it work well on clusters of computers, where each file could fit in memory and you can do scale-out processing of the entire dataset. Generally the best way to split them files up is by the most commonly used data field(s). If you have a bunch of log data then date is an obvious one, so that if you just want to query the last week’s files then it’s a smaller number of files. The footer of each Parquet file easily reports the stats on the data that is contained in it.

With geospatial data the most common queries are usually by the spatial column – you care about where first, and then filter within it. So it makes a ton of sense to break files up spatially. And it also makes a ton of sense to organize the row groups spatially as well. After a decent bit of experimentation I think the pattern looks something like:

- Add a column to act as a spatial index. S2, GeoHash, Quadkey are all good candidates, I think H3, Plus Codes, Placekey all could work too. I’ve been doing Quadkeys at level 12, not out of deep research, mostly because Microsoft is a big Overture supporter and I started with that. It doesn’t have to be a perfect spatial index, but it does need to allow comparisons in a single column. (There’s probably some cool r-tree way to do things, but that’s beyond me for now).

- Add at least one column for the admin boundary. This could be the country and the state/province level, or could be like county level. I think other ways to split it up could potentially make sense for specific domains, like by watershed for stream data. But I think admin boundary is likely the one that most people understand naturally, and you’d need good reasons to split the data on something else.

- Create at least one GeoParquet file per admin boundary. I think ideally you have a number of admin boundaries that are one file, but I suspect it’s important to break larger files up into smaller parts. I’ll discuss that more below, but I think this step is key to make the data useful in traditional GIS workflows – I can go to a directory and see the files I need to download.

- Order your GeoParquet output by the spatial column, and be sure you write it in sufficiently small row groups. I am still shooting in the dark for row group size, but files with 10,000 rows per group performed way better than those with 200,000.

For global datasets I find it really nice to have the data split by country. It’s often what people are looking for, and you can just point them at the file and it all makes sense. And the cool thing is if you just split it up that way then the stats get all nice for any spatial query. It’s ok if it’s a query that spans countries, and if the countries overlap in complicated ways – querying a few extra files isn’t a huge overhead. But the spatial query is able to quickly determine that there’s lots of files that it doesn’t need to actually interrogate.

This is as yet a very ‘broad’ pattern, and I think there’s a lot of things to test out and optimize, and indeed there may be cool new indexing and partitioning schemes that are even better. I suspect that you could optimize purely on spatial position, like just break up files by quadkey, and it’d likely be faster. But my suspicion is that the gain from speed doesn’t outweigh the ‘legibility’, unless you weren’t exposing your core source files at all. There’s a few things I’ve explored, and a number of things to explore more – I’ll try to touch on most of them.

Indices, BBOX and a Columnar Geometry

One big thing to note is that GeoParquet’s geometry definition in 1.0.0 is a binary blob, and thus it doesn’t actually show up in the stats that Parquet readers are using to smartly figure out what they should evaluate. It is a very ‘standard’ binary blob, using the OGC’s Well Known Binary definition, so it’s easy for any reader to parse. But it doesn’t actually enable any of the cloud-native ‘magic’ – the blob just sorta comes along for the ride.

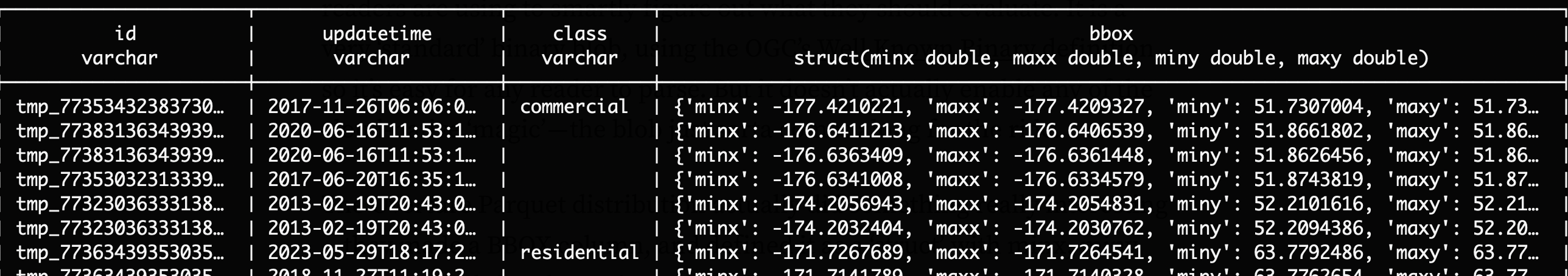

The Overture Parquet distribution actually did something really interesting – they made a BBOX column, and defined it as a ‘struct’ with minx, miny, maxx, maxy defined as points within it.

Since these are in a native Parquet structure they each get stats generated on them, so it actually does enable the cloud-native ‘magic’. You should be able to use those plus row groups like a spatial index to query more efficiently. Just create a manual BBOX query in your WHERE clause (like bbox.minX > -122.5103 AND bbox.maxX < -122.4543 AND bbox.minY > 37.7658 AND bbox.maxY < 37.7715)), and hopefully it’d do the bounds much faster and the more expensive intersect type comparison will happen when the bounds overlapped.

The core Parquet files from Overture weren’t structured at all to provide any advantages from this type of query, however. Each file contained buildings from the entire globe, and then the row groups were clearly not ordered spatially at all, see how they load:

110mb Overture Maps default partition, translated directly to GeoParquet w/ GPQ

Every building everywhere loads at once, meaning each row could be anywhere in the world, so you can’t ‘skip’ to just the relevant part. The experience of watching most geospatial formats load in QGIS is usually more like:

162 mb Overture Maps data, partitioned to Jamaica, data ordered on ‘quadkey’ column w/ DuckDB

This is because most all geospatial formats include a spatial index, ordering the files spatially, so when they load it appears in spatial chunks. The gif below is the same Overture data, in a file that was partitioned to just be Jamaica, and in the creation of the file with DuckDB I added a quadkey column and then my output command was:

COPY (SELECT * FROM buildings WHERE country_iso = ‘JM’ ORDER BY quadkey) TO ‘GY.parquet’ WITH (FORMAT PARQUET);

You actually could drop the quadkey column (SELECT * EXCLUDE quadkey FROM buildings…) and the file would still load similarly. The manual bbox query should still be able to take advantage of the ordering, since it’s now grouped for the row group statistic optimizations to skip data.

I was really excited by having this bbox struct, and in my initial development of the client side tool I thought that I could just query by the struct. But unfortunately the results weren’t really performant enough – it took minutes to get a response. I did make a number of other improvements, trying a number of different things at once, so it’s definitely worth revisiting the idea. Please let me know results if anyone digs in more.

The breakthrough for performance seemed to be just querying directly on the quadkey. Where I landed was doing a client side calculation of the quadkey of whatever the GeoJSON input was. Then I could just issue a call like:

select id, level, height, numfloors, class, country\_iso, quadkey,

ST\_AsWKB(ST\_GeomFromWKB(geometry)) AS geometry from

read\_parquet('s3://us-west-2.opendata.source.coop/cholmes/overture/geoparquet-country-quad-hive/\*/\*.parquet', hive\_partitioning=1),

WHERE quadkey LIKE '03202333%' AND ST\_Within(ST\_GeomFromWKB(geometry),

ST\_GeomFromText('POLYGON ((-79.513869 22.451, -79.408082 22.451, -79.408082 22.573957, -79.513869 22.573957, -79.513869 22.451))')));

NOTE: one thing I do want to mention is that I believe all of these queries should work equally well with GDAL/OGR. I like DuckDB a lot recently, but OGR’s parquet support can query a partitioned dataset, and I believe using its sql functionality will query in the same way

So that worked really well. There are some places on the earth where the quadkey partitions don’t line up that well, like if the area is straddling the border of a really large quadkey. So I’m sure there’s some indexing schemes that could be better, I’m very, very far from being an expert in spatial indexing. Read on for a later section on indices.

The other cool development to mention is that the plan for GeoParquet 1.1 is to add a new geometry format that is a native, columnar ‘struct’ instead of an opaque WKB. This is all being defined in the GeoArrow spec (big congrats on recent 0.1 release!), since we want to be sure this struct is totally compatible with Arrow to enable lots of amazing stuff (half of which I still don’t understand but I’m still compelled by it and I trust the people who know more than me). This will work automatically with the stats of Parquet, and if it works well it may mean we may not need the extra index column for efficient cloud-native queries. But I am interested in getting to at least a best practice paper to help guide people who may want to add a spatial index as a column, as it likely still has uses and it’d be nice to have recommendations for best practices (like what to name the column), so clients can know how to request the right info.

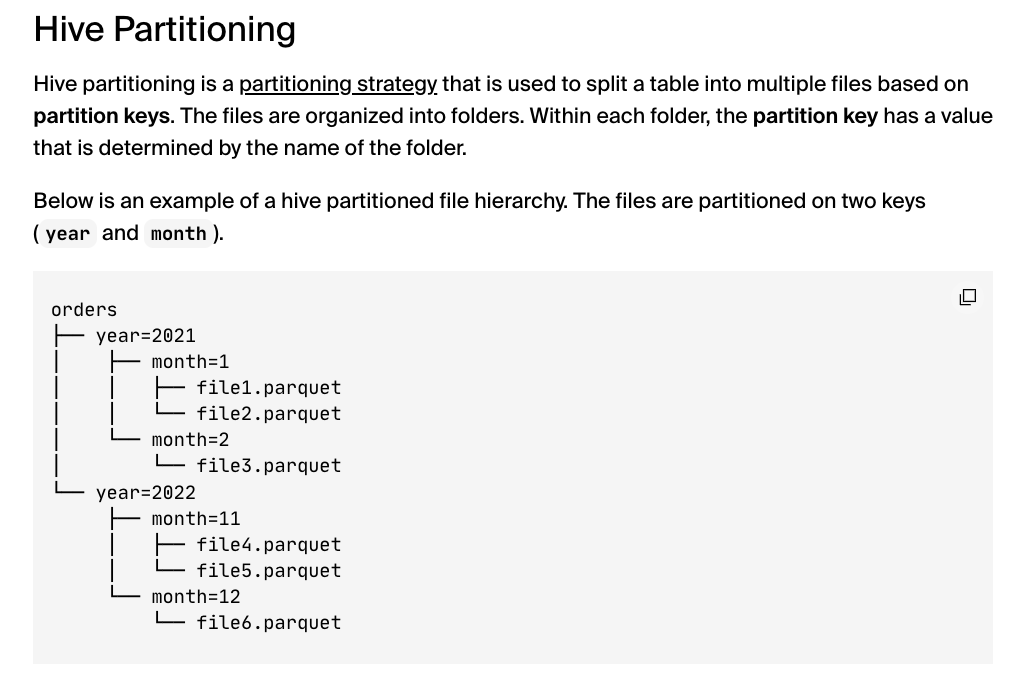

Hive partitions

The other thing I experimented a good bit with was ‘Hive partitions’. These are actually really simple, and very flexible. It’s just a convention for how to encode key information about a folder into the name of the folder.

As you can see it’s a simple scheme, just call the directory

My main experiments were to use ‘country_iso’ as the column to organize the hive partition on. In my first Google Buildings experiment I split up every country in the folder by admin level 1 (state / province), and was pleasantly surprised that all the hive stuff still worked.

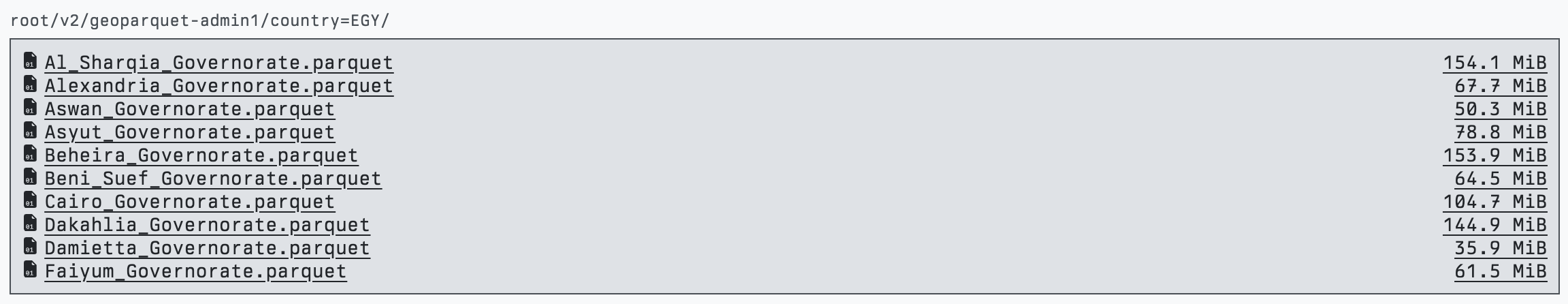

Egypt Partition, with each file split into the admin level 1 entity

Most of the examples and tools with hive do all the ordering and partitioning automatically, and often just have a number of files named data_1.parquet, data_2.parquet. But it was totally fine for me to split them as I liked and name them California.parquet and British_Columbia.parquet and have everything still work the same. If that were not the case then it’d be a lot more difficult to use those hive partitions with traditional geospatial workflows. It does introduce a slightly weird syntax, having folders named ‘country_iso=CA’ (could make it friendly with country=Canada, but still looks a bit odd), but if there’s real performance gains then it’s worth.

I did start to experiment with those gains, and it seemed to be that if you actually do use that column in the query there’s a pretty big benefit. This needs a lot more testing, but in the main test I did performance went from 30 seconds to under 3 seconds. The queries above modified to make use of my hive partition just adds country_iso = 'CU' at the start of the WHERE clause.

select id, level, height, numfloors, class, country\_iso, quadkey, ST\_AsWKB(ST\_GeomFromWKB(geometry)) AS geometry from read\_parquet('s3://us-west-2.opendata.source.coop/cholmes/overture/geoparquet-country-quad-hive/\*/\*.parquet', hive\_partitioning=1),

WHERE country\_iso = 'CU'

AND quadkey LIKE '03202333%' AND

ST\_Within(ST\_GeomFromWKB(geometry), ST\_GeomFromText('POLYGON ((-79.513869 22.451, -79.408082 22.451, -79.408082 22.573957, -79.513869 22.573957, -79.513869 22.451))'))

It does make a ton of intuitive sense why this is faster – without that it needs to issue an http request for the footer of every single file to be sure there’s nothing it needs to interrogate further. So if I know that the query is definitely in Canada then it only has to query the files in that folder.

I did seem to find that if you’re not using the hive partition then the overall queries seem a bit slower. Which also makes sense – without Hive partitions I’d just put all the files in one directory, so with Hive as it’s got to touch S3 for each directory and then each file, instead of just the files.

The way my CLI works right now is that a user would need to supply the country_iso as an option in order to get it included in the query. But it does feel like there could be a way to automatically figure out what the proper country_iso(s) would be. Right now the quadkey gets calculated on the client side, so I wonder if we could just preprocess a simple look-up file that would give the list of country_iso codes that are contained in a given quadkey. No geometries would be needed, just quadkey id to country iso. It seems like it should work even if a quadkey covers multiple countries – it’d still help to use the hive partition. I think this should be a fun one to make, if you want to take a shot just let me know in this ticket.

Admin 0 and 1 datasets

One of the most important pieces to make this work well is great administrative boundaries. Ideally ones that fully capture any area where there’d be a potential building (or other object if we go beyond buldings). And they need to be true open data with a liberaly license. When I started on Google Buildings I used GeoBoundaries CGAZ which worked pretty well. The one issue is that their coastlines are close in and not all that accurate, so it missed a lot of buildings on the coast and on islands.

Doing the ‘nearest’ boundary works pretty well – I used PostGIS, and VIDA used BigQuery in the Google + Microsoft dataset. It feels like it wouldn’t be 100% accurate, so ideally we’d get to a high quality admin boundary that goes all the way to their ‘exclusive economic zones’ and has area for open ocean. I did make an attempt to buffer the CGAZ boundaries, but I haven’t tried it out yet. It’s still not likely to be 100% accurate in all cases – you could see an island off the coast of one state that actually belongs to another one. You can try it out… as soon as I find the time to upload it and write a readme on source cooperative. But just ping me if interested.

I also tried out the Overture admin boundaries. Admin level 0 was quite easy, as there was an example provided in the docs. And it worked much better than CGAZ with the coastlines – it clearly buffers a lot more:

Red is Overture, Green is CGAZ (and slipped in my CGAZ buffer in grey)

I’ve been partial to DuckDB lately, which does not yet support nearest (and probably needs a spatial index first before nearest is reasonable), and Overture managed to match over 99.9% (check this) of the data.

Admin level 1 was more challenging with Overture. I believe most of the world calls states and provinces ‘level 1’, but open street map & overture call it level 4. It was a pretty obscure DuckDB query, but I got results as GeoParquet (I’ll also try to upload this one soon). Unfortunately they’re basically useless for this purpose as they just have a number of states that are totally missing (at least in the July release, haven’t checked October). Maybe they’re in there somewhere and I’m doing it wrong – happy for anyone to correct me and show how to get all the states & provinces. So with Overture I just did admin 0 and then broke the data by quadkey if it was too big. I kept this for my Google Buildings v3, since I had scripts that were very easily adapted and worked with DuckDB on my laptop. But I think there’s still a lot more experimentation to do here.

One thing I did find is you can’t do ‘unbalanced’ hive partitions. It seemed like it could be ideal is to just have country files at the root level and only use the hive partition if the country needs to be broken up. This could be really cool, since you could do that two levels down – like California is often huge and so California could have a folder with its counties available for download, but smaller states would just be a single file. Unfortunately you need to put each file in its own folder for the hive partition to work its magic.

I hope to refine a ‘best practice’ more, to balance the ‘traditional’ GIS workflow of a folder structure that’s intuitive to navigate but also cloud-native performant. The things on the list include:

- Use the country name instead of iso code in the file name (I did this in my last Overture processing – previous ones the file was named the iso code). I used https://github.com/lukes/ISO-3166-Countries-with-Regional-Codes/blob/master/all/all.csv to look up the country name.

- Use 3 character iso instead of 2 character one. My first Google ones did this, but Overture data is 2 character so the latest ones have been that. But 3 character feels more intuitive, and can use the above CSV file.

- Break up large countries by admin level 1. My latest ones broke up large files by quadkey, since I didn’t have admin level 1 working with Overture. But ‘US_032002.parquet’ is a lot less intuitive than ‘Colorado.parquet’. The quadkey I think will ‘balance’ the data better, but I have a hunch the performance hit won’t be too bad, and having the traditional experience more intuitive would be a win. You can’t have unbalanced partitions, but you can have different numbers of files in each directory, so you could have the algorithm use admin level 1 if the country file was over a certain amount (you just couldn’t further break up California into counties in another hive partition. But I just realized you could append the name: US_California_Contra_Costa.parquet, so that could be something to play with.

I’d welcome anyone experimenting with this more. And I think the big thing to do is figure out which of the administrative boundary options is best for this use case. I got a recommendation for Who’s on First, and am open to other options. I think the key thing is to be sure all potential buildings on islands and coastlines are captured.

Row groups & number of files

So what is ‘too big’, so that the file should be broken up, in my previous section? I’ve been using approximately 2 gigabytes as the upper size to cut off and break files into smaller parts. This mostly came because I’m working on a desktop computer and with pandas in particular anything with more than 2 gigabytes or so of data would take up too much memory. And other programs would also perform less well. I think I’ve also heard that in the general scale out data world it’s also a good to keep data smaller than that, so each section completely fits in memory when you process it with a cluster.

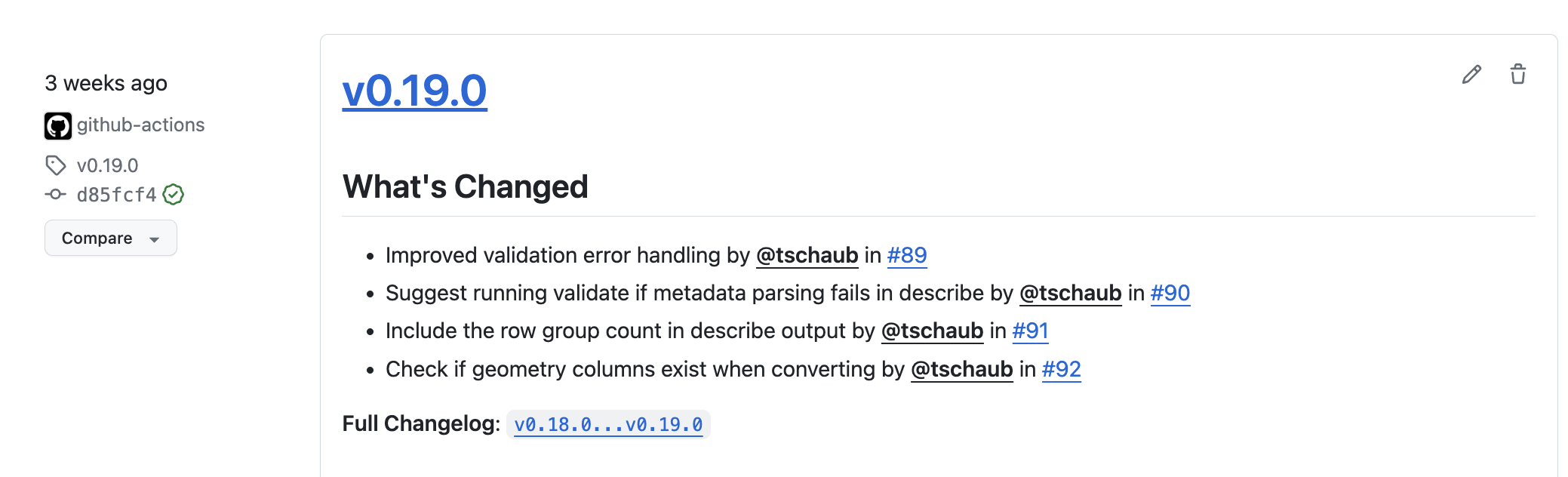

I’ve been using a good bit of Pandas recently since it was the best to set the row group size on data like Overture with nested Parquet data structures. I did attempt to use GDAL/OGR for processing data, since it does let you set row group size and it seems like it should work, but I couldn’t get my OGR code to load the geometry column if the data was not compliant GeoParquet (DuckDB doesn’t yet write out GeoParquet, so I needed a post-process step) any help is appreciated (PR’s welcome ;)). GPQ has been my go to tool, as it does great with huge files and memory management, but it did not yet support control over row group size. But now it does!

So I’m sure I’ll just use GPQ in the future, as it’ll handle much bigger Parquet conversion with ease.

I am curious about the performance of querying large files in a cloud native way, but it does feel a bit more ‘usable’ for a traditional GIS workflow if you’re not having to download a 10 gigabyte file for all of Brazil. So I lean a bit toward breaking them up. VIDA put up both approaches in their Microsoft + Google dataset – /geoparquet/by_country/ has one file per country, with a 12.7 gig US file, and /geoparquet/by_country_s2/ splits by S2. I’d love to see some performance testing between the two (and to get both options added to my CLI) But I think I lean towards sticking to a ~2 gig max per file.

Ok, so what is this row group size? As I mentioned above row groups are these chunks of rows that provide ‘stats’ on the data within them, so the row group size is how many rows are in each chunk. They essentially serve as a rough ‘index’ for any query. And it turns out setting different sizes can make a pretty large difference when you’re trying to query against a number of files. I was using GPQ which set very large row group sizes in early versions. When I switched to Pandas and used a row group size of 10,000 then I got substantially better performance when doing a spatial query against the entire dataset.

I’ve experimenting with different sizes, but I definitely feel like I’m shooting in the dark. I read somewhere that if you have too many row groups per file and you query across a bunch of files then it can slow things down. I hope that someone can experiment with creating a few different versions of one of these larger datasets so we can start to gather recommendations as to what row group size to set, and how to reason about it relative to number of files. Though just last night at Foss4g-NA Eugene Cheipesh (who shared insights from going deep with GeoParquet indexes more than a year ago) gave some hints. He said to think of row groups like a ‘page’ in PostgreSQL (I didn’t really know what that means…), and to aim for 200kb – 500kb for each. The python and go Parquet tools just let you set number of rows, so it’ll take a bit of math and approximation, but should be possible.

I made it so my command line program that creates GeoParquet from a DuckDB database lets you set both the maximum number of rows per file and the row group size. If there’s more than the max rows per file for a given country then it just starts to split it up by quadkey until it finds one that is less than the max rows. I was pleased with my function that splits countries by the maximum number of rows, as it’s the second time in my entire programming career that I used recursion. I would love to have an option that splits it by admin level 1, for a bit more legibility, but I didn’t get there yet.

I also attempted to get it to try to find the smallest possible quadkey, as occasionally the algorithm would select a large quadkey that could likely be slimmed down without splitting into more quadkeys. I am also curious if a pure partition by quadkey would perform substantially better than the admin 0 partition. I’m quite partial to the admin 0 partition for that traditional GIS download workflow, but if the performance is way better and we have a large ecosystem of tools that understands it then it could be an option. And anyone that’s just using GeoParquet to power an application without exposing the underlying partition may prefer it.

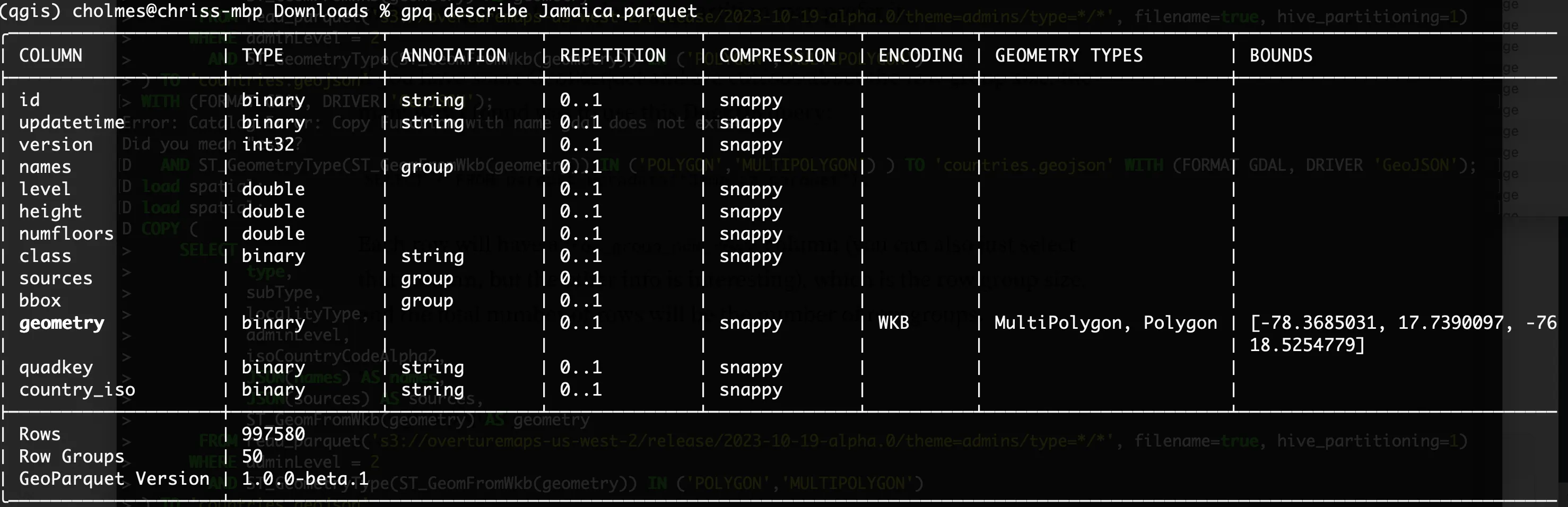

If you have some GeoParquet and are curious about the row group size, the main way I found was to use this DuckDB query:

SELECT * FROM parquet_metadata(‘Jamaica.parquet’);

Each row will have a row_group_num_rows column (you can also just select that column, but the other info is interesting), which is the row group size. If you want the number of row groups use SELECT row_group_id FROM parquet_metadata(‘Jamaica.parquet’) order by row_group_id desc limit 1;and add 1 (0 is the first id)

GPQ’s ‘describe’ also now includes the total number of rows and the number of row groups:

There may be other ways as well, but those both worked for me.

Spatial Indices

The other area that would be great to see more experimentation in is with is spatial indices. I picked quadkeys, and the choice was fairly random. And I wouldn’t say it works perfectly, as some of my sample GeoJSON queries would span borders of ‘big’ quadkeys, so the quadkey that would fully contain my query would be a level 3 quadkey, like 031, which covers a large chunk of the earth.

So obviously the query would have to perform the spatial filter against a much larger set of candidate data. Perhaps other indexing schemes wouldn’t have that issue? And actually as I write this it occurs to me that I could attempt to have the client side figure out if a couple smaller quadkeys could be used, instead of just increasing the size of the quadkey until the area is found. But I suspect that other indices might handle this better.

I would love to see some benchmarking of these single column spatial indices, and also any other approaches towards indexing the spatial data. And I’m open to people pointing out that my approach is sub-optimal and proposing new ways to do it. The thing that has been interesting in the process is how you can get increased spatial performance by just leveraging the existing tools and ecosystem. I’m sure a DuckDB-native spatial index would perform better than what I did, but I was able to get a big performance boost on remote querying spatial data just by adding a new column and including it in my query. It’s awesome that the whole ecosystem is at the point of maturity where there are a number of different options to optimize spatial data.

I also understand that this scheme isn’t going to work perfectly for all spatial data. Big long coastlines I’m pretty sure will break it, or huge polygons. But many of those I don’t think need to be partitioned into separate files – it’s fine to just have one solid GeoParquet file for all the data. I see this as a set of recommendations on how to break up large datasets, but those recommendations should also make clear when to not use it.

Table Formats

I’ve not yet had the time to really dig into ‘table formats’, but I’ve learned enough to have a very strong hunch that they’re the next step. The idea is that with some additional information a bunch of Parquet files on the cloud can act like a table in database – giving better performance, ACID transactions, schema evolution and versioning. There’s a few of these formats, but Apache Iceberg is the one that is gaining momentum. This article gives a pretty good overview of table formats and Iceberg. And Wherobots just released the Havasu table format, which builds on Iceberg and adds spatial capabilities, using GeoParquet under the hood. I’m hoping to be able to add a table format to the ‘admin-partitioned geoparquet distribution’ to help even more tools interact with it. I’ll write a blog post once we get some results – help on this is appreciated!

Where to from here?

Ok, so this is now a long ass blog post, so I’m going to work to bring it to a close. I think there’s a number of potentially profound implications for the way we share spatial data. I just gave a talk at Foss4g-NA that explored some of those implications. The talk was recorded, so hopefully gets published soon. But if you’ve made it all the way through this blog post you can peruse the slides ;) Lots of pictures and gifs, but the speaker notes have all that I said. Since it’s a talk I had to keep things quite high level, but I’m hoping to find time in the next few months to go a lot deeper in blog posts.

There are clearly lots of open questions throughout this post. My hope is that we could get to a recommended way for taking large sets of vector data and putting it on the cloud to support traditional ‘download’ workflows, cloud-native querying, and everything in between. I’m pretty sure it’ll be partitioned GeoParquet + PMTiles + STAC, plus a table format. And we should have a nice set of tools that makes it easy to translate any big data into that structure, and then also lots of different tools that make use of it in an optimized way.

I’d love any help and collaboration to push these ideas and tools forward. I’ve not really been part of a proper open source project in the last ten years or so, but we’ve got a small group coalescing around this open-buildings github repo where I started hacking on stuff, and then also on the Cloud-Native Geo Slack (join with this link, and #admin-partitioned-big-data is the channel centered on this). Shout out to Darren Weins, Felix Schott, Matt Travis, and Youssef Harby for jumping in early. I think one cool thing is that the effort is not just code – it’s evolving the data sets on Source Cooperative and putting more up, enhancing code, and then I think as it starts to coalesce we may make some sort of standard. I’m not sure exactly how to organize it – for now the Open Buildings issue tracker just has a scope beyond code. It’ll likely make sense to expand from this that repo, indeed we’re already doing more data than just buildings.

But please join us! Even if you’re not an amazing coder – I’m certainly not, as it’s been 15+ years since I coded seriously, but ChatGPT & Co-pilot have made it possible. New developers are welcome, and there will also be ways to help if you don’t want to code.

Our blog is open source. You can suggest edits on GitHub.